Mark Rowlands has come of age. His hair is dyed, he is not a lonesome writer anymore but a reknown professor of philosophy at the University of Miami, a husband and a father. And instead of a wolf, a Schaeferhund-dog is now his companion on his daily jogging trips.

Mark Rowlands has come of age. His hair is dyed, he is not a lonesome writer anymore but a reknown professor of philosophy at the University of Miami, a husband and a father. And instead of a wolf, a Schaeferhund-dog is now his companion on his daily jogging trips.

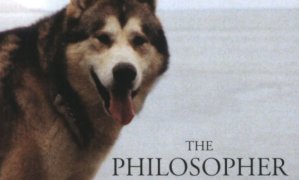

The wolf made Mark Rowlands famous. “The Philosopher and the Wolf” oscillates between macho-myths of a man and his beast and academic philosophy, an autobiography and an analysis of ethics, communication and the meaning of life, an instructional textbook and a pet story more touching than Lassie, Flipper and Black Beauty.

“The Philosopher and the Wolf” describes eleven years Rowlands spent as a philosophy teacher and writer in Alabama, Ireland and France, always accompanid by a wolf he bought in his early twenties. During all these years, men (and women) appear only as marginal characters in Rowlands life, no matter if he’s having years of party in Alabama, a hermit’s life in Ireland or a merry bachelor’s life in southern France.

The solitary way of living, the intense examination of the world, view and values of animals directs Rowlands to ask fundamental questions on what is important, what is good and bad, what is happiness, and finally: What does death mean for men and for animals?

The book is more than just a pet story – although that might be hard to get for readers who never even had a hamster. The death of pets is a strong experience n0ot only because we probably liked them, but because it signifies the end of quite long period in our life that we overlook from end to end. We have been there before our oets, and we are still here, while a whole life has passed. The death of a dog reminds us very clearly that now 10, 12 or fifteen years have definitely passed, are gone, will never come back again, that we will have to change some habits and probably think of something new.

Thoughts on the meaning of death for men and wolves (or dogs) cumuluate in the last chapter of the book, “The Religion of the Wolf”. Men fear death, they Rowlands, because they think about the future. That’s the problem with dying: It’s not that we loose what we are or have, the problem is that death makes us loos our future.

Wolves (or dogs or other animals) don’t care about past or future – they are just know They know neither hope nor fear, they just care about what’s going on right now – which after all, is a very decent way to handle things…

“The Philosopher and the Wolf” is a very beautiful book combining a nice story with practically explained philosophical topics. The public reception was somehow different: Journalists liked it, the book sold great – but the reviews mostly focused on the macho-aspect of living a merry bachelor’s life with a wolf – or on the unpleasant part of having to sort out fights with other dogs, dealing with the lust for destruction of young wolves (dogs) and having to take care of a sick and dying wolf (dog).

That’s not the story – we should know this if we ever had a hamster….

The view and insight Rowlands describes, is an extended, enhanced view that acknowledges the presence and specific intelligence of other beasts than men.

This is a perspective we are not used to; in our daily world, the idea that the rest of the world – environment, animals, nature – are not there for us, at our disposal, but that it is with us – or actually the other way: We are allowed to be with them.

I bet it’s not pure chance that Rowlands is not only the guy with the big dogs, but also one of the most prominent philosophers in the field of animal rights – and a representative of the philosophy of the external mind. Wikipedia says he is “one of the architects of a view known variously as the extended mind, vehicle externalism, locational externalism, active externalism, architecturalism and environmentalism.”

“The idea, very roughly, is that at least some mental processes extend into the subject’s environment in that they are composed, partly (and, on most versions, contingently), of manipulative, exploitative, and transformative operations performed by that subject on suitable environmental structures”, explains Rowlands. “I think I’m also known for holding a rather strange view of the nature of consciousness.”

Interview

Michael Hafner talked to Mark Rowlands about morality, mortality, loneliness as a merry bachelor’s life and the questions wether fleas have feelings. and other moral obligations towards animals

themashazine: After reading “The Philosopher and the Wolf” I head tears in my eyes and started to louse my dog, because I just wanted to do her something good. – Actually, I thought I would not like the book after I read some (mainly german) reviews that gave me the impression of you as someone exploiting something quite ordinary (living with an animal) as something special and exciting (the big, strong, mean, stinking, aggressive and then even ill animal). – How did you like the reception of your book?

Mark Rowlands: I’m not familiar with the German reviews, as I don’t speak German. I suppose I am aware of most of the English language reviews (my publishers send them to me), and, of course, I’m delighted – since the vast majority of them have been very positive. I try – I really try – not to take any notice of reviews: but it’s much easier to do that when they are so nice!

themashazine:what can people who never lived with an animal take from your book?

Mark Rowlands: The book is an extended examination of what it means to be human. In particular, I examine three features that are thought to separate us from other creatures: intelligence, morality, and our understanding of our own mortality. So, the book would be, I hope, of interest to anyone who has thought about this issue – whether or not they live with animals.

We are more intelligent than other animals (at least in the way we measure this). But this comes from our simian forebears travelling a path that wolves and other social creatures did not. Our intelligence is grounded in more primitive abilities to manipulate and deceive our peers. The result was an arms race, where abilities to resist manipulation and deception just about kept their noses in front of manipulation and deception. The intelligence we have today is a result of this race: manipulation and deception are core components of human intelligence.

This theme was reiterated in my discussion of morality. We are also distinguished from other creatures, so we think, by our moral sense. We understand right and wrong: they do not. I examined the extent to which power and deception lie at the core of our sense of right and wrong. So, for example, take a social contract model. The basic idea is: you scratch my back, and I’ll scratch yours. Or, at the very least, you refrain from sticking a knife in my back, and I’ll similarly refrain. You accept certain limitations on your freedom if others will accept the same limitations. Morality emerges from these sorts of primitive (and hypothetical) agreements (or contracts). However, as many have pointed out, it makes sense to contract only with people who are capable of helping you or hurting you. Therefore, if this is the basis of morality, those who can do neither fall outside the scope of morality. That is: we have no moral obligations to the powerless. Power is deeply embedded in the way we think about morality.

The same is true, I argued, of deception. In the contract, image is everything. It doesn’t really matter whether you are helping someone else, as long as they think you are. If you can deceive, you garner all the benefits of the contract whilst accruing none of the costs. The contract, by its nature, rewards deception. So, while the contract is supposed to be about morality, if you dig a little deeper, you find power and deception.

Our sense of our mortality is perhaps the most decisive difference between us and other creatures. I think other creatures understand death only in part. They cannot understand the ‘and that’s all she wrote’ aspect of death. That the one who dies will return nevermore. Because we can realize this, in a way that no other creature truly can, we have a choice to make – one so fundamental that it effectively defines the kind of life we are going to live. We can tell ourselves stories to the effect that death is not really the end. The basis of the stories is hope; hope that becomes the primary virtue of some religions and re-baptized faith. Hope, I said, is the used car salesman of human existence: so friendly, so plausible, but you can’t rely on him.

Why did I say this? Hope takes away something from us – it takes away the possibility of our lives possessing a certain kind of value. There are certain moments, I argued, when we are at our best; and it is here that the real value of life is to be found. This value is not to be found in goals toward which we strive, our ambitions, achieved or not. Our lives resist judicial summary. Rather it is to be found at certain moments, scattered around our lives. This talk of moments confused a lot of people, and led them to the conclusion that I was saying we should live in the moment. In fact, I said the opposite: living in the moment is not the life characteristic of a human – and there is no point trying to be what we are not. So, let’s replace the word ‘moments’ with ‘times’. There are certain times in our lives when we are at our best. This is when we understand the game is up. These are the times when hope has deserted us, and we have nothing left but our defiance and our scorn. In the end it is this defiance that gives our lives value: it is only our defiance that redeems us.

themashazine: What do you tell people who say they feel the same you felt about Brenin (the Wolf) about their Chihuahua?

Mark Rowlands: Good question. I attach no direct significance at all to the fact that Brenin was a wolf (or maybe wolf-dog mix). For the purposes of the book, it really did not matter. Could someone feel the same about their Chihuahua? Yes, they certainly could.

themashazine: You describe yourself as a misanthrope – what made you change your mind? did you change your mind or did you find a way to live with it? has something changed since your obvious misanthrope-times?

Mark Rowlands: Looking back, I tend to think that I just wanted a break from human beings for a while. Does that make me a misanthrope? Maybe it does.

themashazine: Your life in Ireland and France does not sound uninteresting for a man; one could get used to it as a merry bachelor´s life – but who did clean your house and do your laundry at that time?

Mark Rowlands: I cleaned my house and did my laundry. The laundry was fine, but the house was rarely clean – although, in my defense, I did have three large, and often muddy, canines sharing a small cottage.

themashazine: I like your arguments about morality and the attitude towards the weak. But are not also intentionality and the perceived distribution of power important issues? Are my horses – who are way stronger than me – mean when they step on my toes? Are they immoral when they risk my health by jumping around and hustling me, when they are scared of green Martians they see in the trees?

Mark Rowlands: Do your horses often see green Martians? If so, what sort of grass is growing in their field?

More generally, animals are not moral agents in this sense: they cannot be morally censured for what they do. They have no choice in the matter, and they cannot subject their actions to critical scrutiny and moral evaluation. That is: they cannot ask themselves questions like: is what I am doing the morally right thing to do in these circumstances?

So, animals are what is known as moral patients as opposed to moral agents. This means, very roughly, that they have rights but not responsibilities. The same, of course, is true of many humans – young children being an obvious example.

Some people claim – usually because they haven’t thought about what they are saying – that you cannot have rights without responsibilities. If they really mean this, then they are committed to denying that young children, and certain other categories of humans, have rights – not an option I would endorse.

themashazine: I guess that my dog is happiest, when she is eating, sleeping in the sun or fighting (which I can’t let her do, because she is too talented and efficient). She can enjoy that until she does something else, I can enjoy – whatever I enjoy – only inbetween (before I have to leave, after I come home from work, because I can take a few minutes now, because we have not sat together or been for a walk or a while now),

Is that part of the difference between wolves and apes you described? And did you find a way to deal with it – or could you just diagnose the difference?

Mark Rowlands: I think it’s true that one of the reasons we humans are such a dissatisfied species is because we are so spread out in time that we find it very difficult to enjoy the moment. As I said: Living in the moment is not the life characteristic of a human – and there is no point trying to be what we are not.

themashazine: Finally, to get back to the fleas: I’m killing them intentionally and they are way smaller and weaker than my dog or me. – Are we immoral?

Mark Rowlands: Two responses:

First, you have a duty of care to your dog that you don’t have to her fleas. You took on that duty when you brought her into your life.

Second, fleas are, as far as know, non-sentient. We might be wrong about this, but given everything we know about the neural basis of consciousness, it’s a pretty good bet. Therefore, a good case can be made for thinking that fleas fall outside the scope of morality. We have no moral obligations to fleas.